Stories: Albert C. Stewart

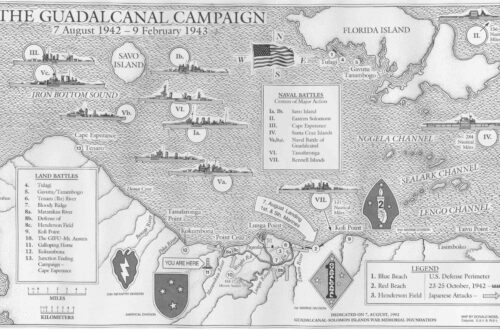

Albert C. Stewart was one of only a handful of Black officers in the Navy during the WWII era. He served as a Lieutenant at the tail end of the war in the Pacific Theater on the fleet oiler USS Sabine.

Initially, Stewart was drafted to be a weatherman for the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African American pilots and airmen who fought in WWII as part of the Air Force. However, the military already had the two Black soldiers who would serve as weathermen, so Stewart was put back in the general draft list. In the meantime, he graduated from the University of Chicago.

Unlike white college graduates, who went immediately to officer training if they were drafted in the Navy, Stewart had to go through boot camp at Great Lakes Naval Station. After Stewart completed boot camp, a white officer said that he should take an officer’s training exam, which he passed. He then went on to Notre Dame University, where he was the only Black midshipman in a class of about 1,300 men training to be officers.

At Notre Dame, Stewart faced opposition from other trainees who couldn’t imagine a Black man being an officer, but “the guys who didn’t like Blacks just mainly stayed away from me.” His only really unpleasant experience, he said, was when a couple of classmates tried to rough him up during a game of touch football, which they played for exercise. “But I roughed them up instead,” he said. His officers were also able to single him out easily and knew him by name, as he was the only Black trainee in the class.

Stewart didn’t anticipate leaving the United States after graduating from Notre Dame in 1945, as there were only thirteen Black officers in the Navy at the time. However, he was assigned to the USS Sabine and arrived just after Japan surrendered. The officer of the deck first mistook him for a steward’s mate as the uniforms for steward’s mates were the same as officers, just missing the gold braid that denoted an officer. He was stunned that there was a Black officer onboard, but luckily it was a kind of “happy stunned” as Stewart described it. Most of the other men were just glad to have replacements so that they could go home.

“The only guy who was really unkind to me at the start was the second in command,” said Stewart. “He was an old Navy guy, had been in the Navy 25 or more years, and had been promoted to an officer because of that long service. And he just couldn’t imagine a Black being an officer. And he cursed me.”

Stewart challenged the officer to a customary way of settling disagreements onboard, which was to go down to a pump room and have a fight. But the officer refused to go. “So everybody knew that he was now not living up to what was the custom, so he was the one in disgrace, not me,” Stewart said. That officer was the only person who really gave him trouble, as the sailors underneath him could be court martialed for disrespecting an officer. At one point Stewart met another Black officer who had faced racist bullying from fellow officers, but luckily that was not Stewart’s experience.

Stewart was the second division officer, who was in charge of the mid-ship to the aft. He was also the athletics officer, which meant that he created exercises for the whole crew, not just his division. He oversaw training for a boxing team and other athletic teams along with his regular officer duties.

As Stewart went into the service after the war had ended, he never saw combat. But casualties were still possible on the Sabine because of dangerous jobs during daily work. At one point, they had to put a line from the ship to a buoy in rough waters – the result of a typhoon in Hawai’i. Stewart elected to do the job himself as he didn’t want his men to get drowned while he was commanding; he had to tie the line while the buoy was above water before it bobbed below. “I got all wet, and the doctor gave me some medicinal brandy to warm me up,” Stewart laughed.

One of Stewart’s happiest memories of the service was when sailors told him that he was their favorite officer as they were going home. “When you’re in that close contact, you know, it’s pretty nice to have the guys say, ‘I’m under your command but you’re a great guy.’ That was a happy feeling.”

He kept in contact with his family through letters which were censored, but a few of his sailors called his mother in Chicago after they were discharged to let her know that he was doing fine.

Once he was discharged, Stewart went back to his home in Chicago. “I do remember that the captain wrote a glowing review of my performance,” he said. “And I felt that he was doing it because here was a new thing, a Black officer, and he was showing his adaptability. I didn’t think I was that good, but he said I was.”

Stewart went back to school at the University of Chicago, where he got his master’s in chemistry in 1948. In 1951, he earned a Ph.D. in chemistry from St. Louis University, where he was “the first Black Ph.D. in Missouri by fifteen minutes” as his graduation ceremony came before the other Black scholar in sociology. He went on to a career in academia, teaching chemistry and physics and serving as both associate and acting dean. In 1999, he became Professor Emeritus at Western Connecticut State University. He also worked in chemistry for thirty-three years at Union Carbide Company.

Stewart passed away on October 13, 2016. In addition to his contributions to the Veterans History Project, he was also interviewed for the HistoryMakers, a digital repository that documents the experiences of African Americans.

This post was written by Wayne State University Graduate Student Erika Purdy.