Stories: Melvin Horwitz

Melvin Horwitz was in an unusual position at the start of the Korean War. Just 24, Melvin had already graduated from Harvard Medical School and had nearly completed surgical training at Yale. However, a wartime draft had been declared. Horwitze could either volunteer his medical services as an Army surgeon, or run the risk of being drafted as a rifleman, an outcome he hardly relished.

Interviewer:

Would you have rather stayed in America?

Melvin Horwitz:

Oh, sure. I’m a devout coward. They were using real bullets in Korea.

But in 1952, Melvin volunteered. His basic training in San Antonio was relatively relaxed. Doctors weren’t expected to achieve a high level of martial discipline or develop combat skills:

As for medical training, they’d already received it prior to enlisting. Soon after, Melvin found himself on a long flight across the Pacific.

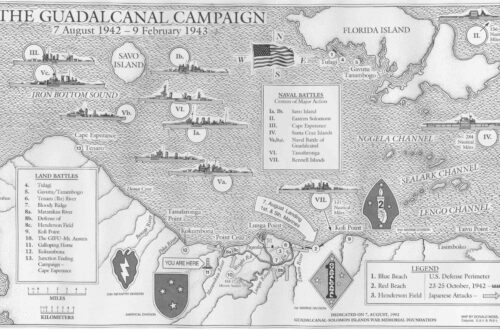

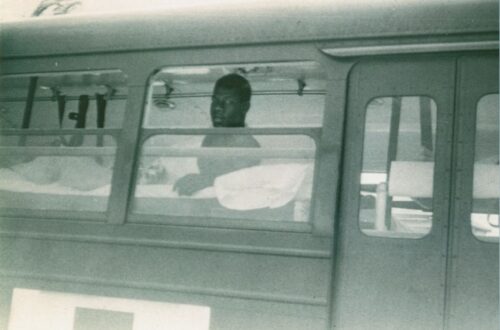

From Japan, a boat delivered Melvin to Incheon and the Korean War. The war’s early years had been marked by high drama: North Korea’s sudden invasion, the dramatic arrival of UN forces under MacArthur, and the surprise entry of China into the war. By 1952, the conflict had settled into a stalemate near the pre-war border.

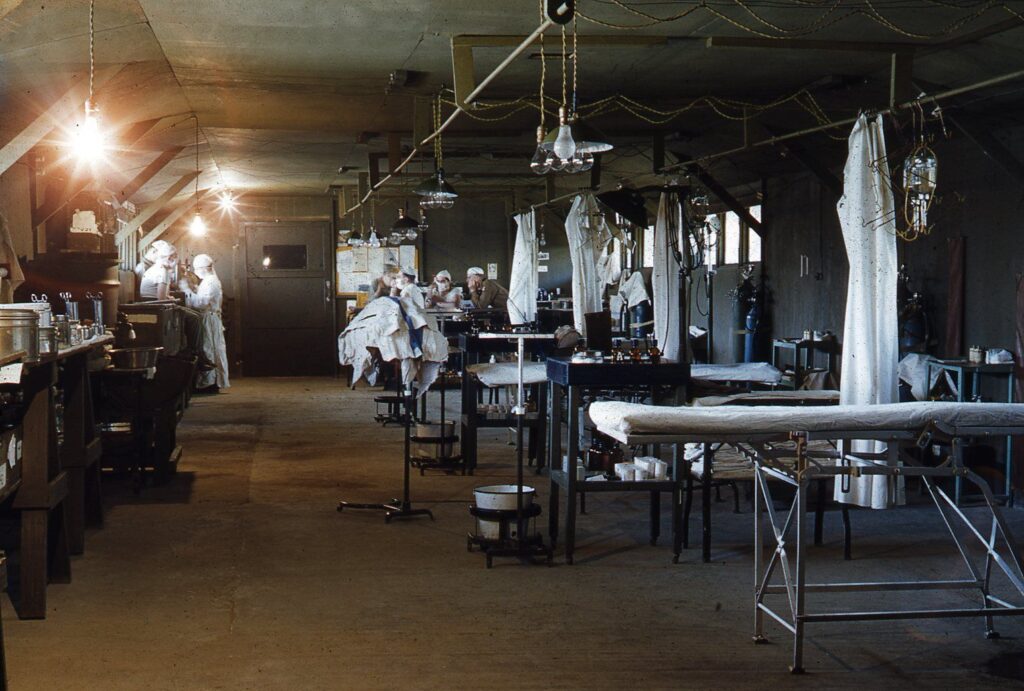

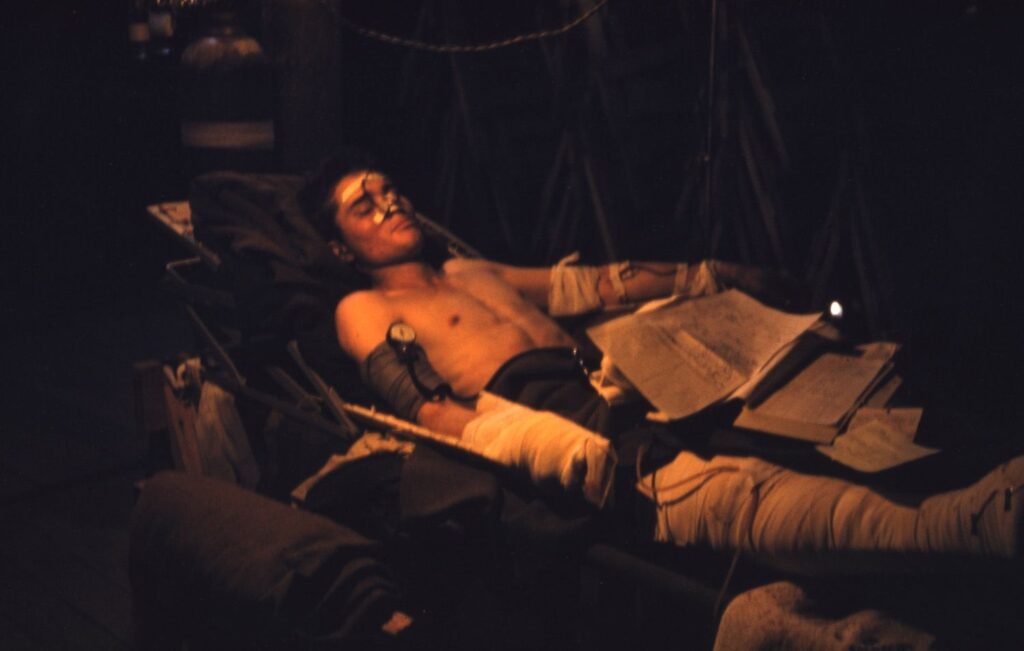

Melvin Horowitz arrived in his first MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) just northwest of Seoul. These temporary surgeries were erected 10 – 15 miles behind the front lines, and wounded soldiers arrived by helicopter during the day, and ambulance at night.

The goal of surgeons like Melvin was to stabilize each patient before they travelled to a fully equipped hospital in Japan for comprehensive treatment.

The work took some getting used to, especially given its relentless nature. Some days were busier than others, but the work was always intense.

Melvin was transferred from one MASH to another, each time entering a similar world of routines and wounds. Every day was spent waiting for the sound of approaching helicopters…

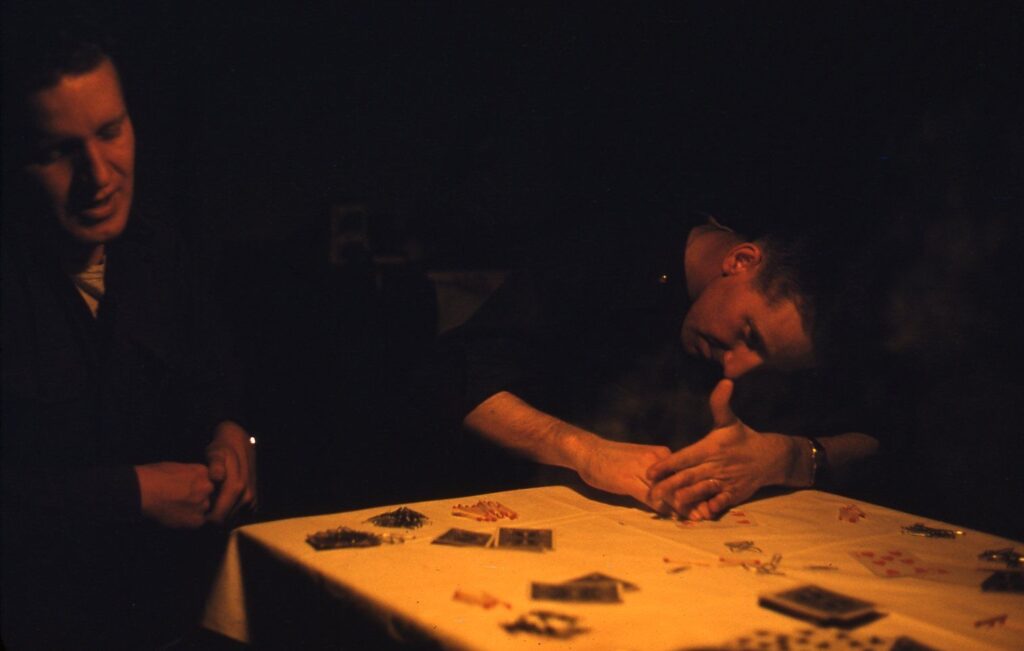

Communication with the Homefront offered some comfort. Melvin and his wife exchanged letters constantly, and their collected correspondence was published after the war.

From the beginning, Melvin had a distaste for war. The relentless work demanded excellence from each surgeon, providing useful experience. At the same time, each teenaged patient – friend or foe – increased Melvin’s loathing for war.

Some serious scares came when the battlelines drew close. Once or twice, Melvin’s MASH was “overrun” by fighting, sending everyone diving for cover:

Some reassurance could be found in the success of Melvin’s work. The timely surgical interventions pioneered in Korea made a tremendous difference, saving many lives by making intensive medical care – like blood transfusions – more immediately accessible.

After a year of MASH, Melvin earned a chance to serve in the rear. He passed the second year of his service in a Japanese hospital, providing comprehensive care for wounded soldiers. Besides the comforts of an actual hospital and a rented house, Melvin’s wife was able to join him in Japan. She taught in Kyushu University and on the Army base, teaching both children and GIs.

In 1953, the international diplomacy finally bore fruit, and peace broke out. The armistice that endures today halted the flow of casualties under Melvin’s care.

Melvin and his wife went home, cherishing some new friendships and a few funny memories:

Most of all, Melvin came away thoroughly disgusted by war.